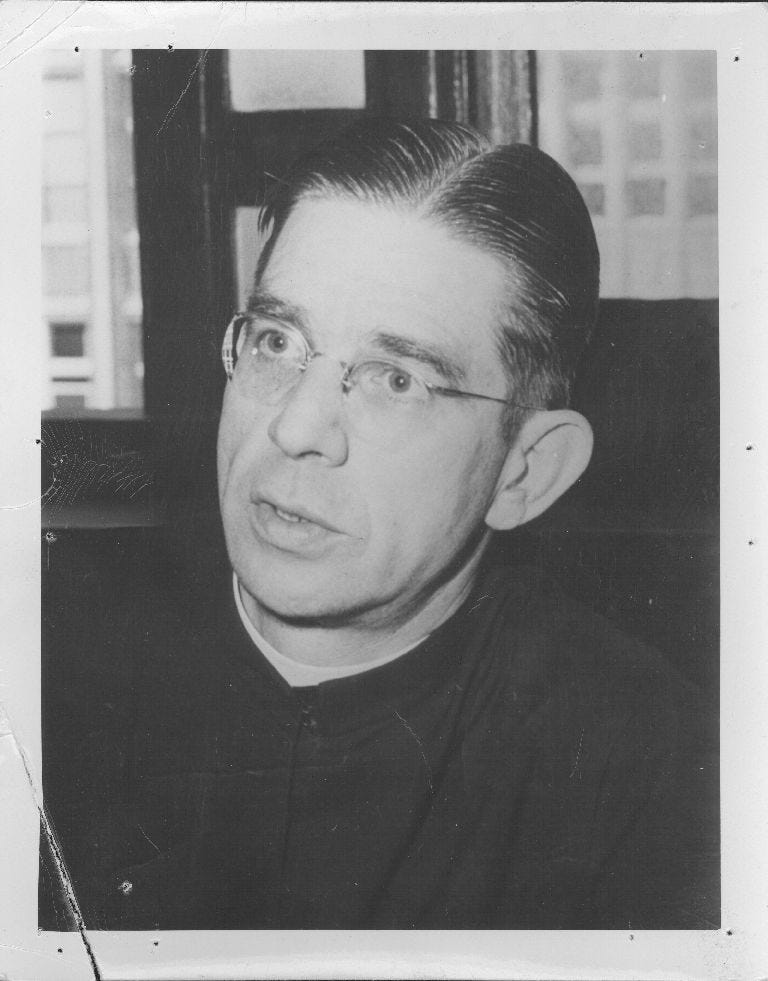

I’m delighted to have you on board as I begin something I’ve never done before: sharing my research-in-progress with the public as I work on a project that greatly excites me: a biography of Father Louis J. Twomey, SJ (1905–1969), whose work for the rights of working people and African-Americans led people to call him “God’s Gadfly in the South.” Subscribe to receive at least one full-access post a month (for unpaid subscribers) or weekly posts (for paid subscribers).*

Here’s why Matters Twomey matters to me:

When my biography of Father Edward Dowling, SJ (Father Ed: The Story of Bill W.’s Spiritual Sponsor) received widespread acclaim and numerous awards (including a 2023 Christopher Award), I took it as a sign that I should continue to do what I now realize I do best: tell the life of a great 20th-century Jesuit. The obvious subject was Father Twomey, who successfully challenged his religious order—and humanity at large—to put its belief in human dignity into action.

A visionary who had a global impact

Inspired by the social-justice encyclicals of Leo XIII and Pius XI, Father Twomey felt a powerful calling to champion the rights of organized labor, the poor, and African-Americans suffering injustice in the segregated South. In 1947, he founded the South’s only labor school, the Institute of Industrial Relations at Loyola University in New Orleans. The following year, he began publishing Christ’s Blueprint for the South, a monthly newsletter sharing his vision of social justice with fellow Jesuits around the world. Its credo: “to create a society in which the dignity of the human person, in whomsoever found, shall be acknowledged, respected, and protected.”

It was a time when Jesuits wielded outsize influence in the Catholic intellectual world and beyond—and the Blueprint influenced the influencers. Over the twenty-one years of Twomey’s editorship, the newsletter’s subscriber base grew to encompass three thousand Jesuits in forty-four countries. Among its readers was Ian Travers-Ball, who credited the Blueprint for inspiring him to serve the poor in India with Mother Teresa; as Brother Andrew, he became the first superior of the Missionaries of Charity Brothers.

Although there are two studies on Father Twomey by Jesuit scholars, there has never been a full-length published account of his life. Moreover, no published author has yet discovered what I have discovered: Twomey’s allyship of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Twomey’s passion for justice led him to become one of King’s earliest white allies, as well as the first Catholic priest to offer the young minister both moral and material support. Evidence of the men’s friendship exists in ten years’ worth of letters from King that were hidden for more than fifty years until Father John Payne, SJ (who wrote his dissertation on Twomey), provided me with copies. (Sadly, the originals were removed from Loyola University New Orleans’s archive by a former Twomey colleague who wished to have them in his personal collection. I have learned that they were later washed away in Hurricane Katrina.)

King and Twomey became friends during a visit that the young Baptist scholar made to New Orleans in early April 1954, before he completed his doctorate and even before he pastored a church. For more than a decade, Twomey advised King on Catholic issues, providing him with literature to help him persuade Catholics of their obligation to pursue racial justice.

Sadly, many Catholics needed such persuading. Formed in an age of populist demagogues such as Father Leonard Feeney and Father Charles Coughlin, these members of the faithful grasped (correctly) that Catholicism stood in opposition to communism. But they felt no religious obligation to oppose racial prejudice. Among them were thought leaders such as National Review’s William F. Buckley, who went so far as to portray the fight against segregation as a dangerous distraction from the fight against communism.

Father Twomey confounded complacent Catholics by insisting that white supremacy, in presenting America to the world as a land of inequality, only served to fuel communism’s spread. To Buckley, such an argument was “nonsensical.” Others used harsher words. Father Twomey told a 1953 Teamsters gathering that white supremacists called him a “Red in Robes” (the “robes” being his cassock), a “racial fanatic,” a “dangerous man,” and a “n----- lover.” He added that he did not fear such “intemperate epithets. But he did fear that “the gross injustices which are inherent in our interracial relations in the South” would bring down “the avenging wrath of an angry God.” As he put it in a 1950 speech to Catholic educators, “How long is God going to allow his image and likeness in black skin to be kicked around?”

By far the most painful opposition Twomey faced was from members of his own Jesuit community. From 1950 onward, he tried repeatedly to convince Loyola New Orleans to admit talented Black candidates to its law school, finally succeeding in 1952 with the admission of Norman Francis (who would become the first Black president of Xavier University of Louisiana). In the Jesuit residence where he lived, Twomey’s neighbors included pro-segregation priests who resented him as a troublemaker. One of them complained to the provincial superior that, thanks to the influence of Twomey and his colleagues, young Jesuits studying at Loyola “had racial equality pumped into them.” But Twomey persisted, and was ultimately vindicated in the most dramatic way possible.

In 1967, Jesuit Superior General Pedro Arrupe summoned Father Twomey to Rome to be the main drafter of “The Interracial Apostolate,” a letter to the U.S. Jesuits urging them “to preach, to teach and to practice the Christian truths of interracial justice and charity.” The Jesuits’ present work promoting those truths can be directly traced to the influence of that letter—the first under Arrupe’s name to emphasize what would become known as the preferential option for the poor.

Father Twomey’s hour is now

The massive media coverage that greeted Rachel L. Swarns’s recent bestseller The 272: The Families Who Were Enslaved and Sold to Build the American Catholic Church demonstrated that audiences are extremely interested in the question of what the Catholic Church, and particularly the Jesuits, have done—or failed to do—in the cause of civil rights for Black Americans. Now that those topics have entered the foreground of the national conversation among readers, the time is right for a book about a priest who awakened the conscience of the Jesuits—and, through them, the US Church—so that they might lead rather than lag in the promotion of racial justice.

In other words, we have heard about the villains in the Catholic Church with regard to civil rights; now, let us hear about a hero—one who helped bend history’s arc toward justice, to borrow a phrase from his friend MLK.

A job for a “mendicant biographer”

The bottom line is that Father Twomey’s story deserves to be told, and it deserves to be told well. So I have written a proposal for the biography, with the working title God’s Gadfly: Father Louis J. Twomey, S.J.’s Battle for Human Dignity in the Deep South, and a publisher is currently reviewing it. [Update, 3/7/24: Since this post originally went up, I’ve given the project a new working title.]

With that said, I am not waiting around for a publishing contract before beginning my work. During the past several months, when not on the road giving talks on Father Ed, I have been conducting extensive original research. Thus far, I have spent a month researching Twomey’s papers in his official archive at Loyola University New Orleans, and am set to return there to complete my research during three weeks in January 2024. In addition, I have conducted research at the Jesuit Archives in St. Louis and at the Amistad Research Center in New Orleans, and in mid-December I will travel to Rome to learn what the Jesuit Curia’s archives hold on Twomey. Other archives that I have consulted include the Archdiocese of New Orleans and the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Archive at Boston University.

I have also interviewed numerous people who knew Father Twomey personally, and I intend to interview many more. To that end, I have placed an ad to run in the December 2023 and January 2024 issues of America magazine to let older Jesuits and others who may have encountered Father Twomey know that I am seeking their recollections of him.

The effort involved in doing this level of research can be personally taxing—especially when I am simultaneously seeking a full-time university-teaching position. I don’t know of anyone else who has attempted this sort of project without a major grant or other institutional support. But I feel a strong vocational call to pursue this project. A friend put it well when he called me a “mendicant biographer.”

Writer’s block, begone!

Although I need to raise funds if I am to fulfill my dream of completing the biography, I expect that Matters Twomey will be a great help to me regardless of whether its paid subscriptions number thirty or thirty thousand. That’s because, with so much research already completed, and without the benefit of a regular position to force me to budget my time, I need something to give me structure in my daily work routine. If you subscribe to this newsletter, your interest in Father Twomey’s life will give me the impetus I need to transform a mountain of source material into a captivating book that will make important contributions to Catholic/Jesuit history as well as the history of the civil-rights movement and of organized labor in the South.

So, thank you for reading this far. I hope you’ll stick around. Father Twomey was a fascinating priest whose courageous witness transformed people’s lives. I can’t wait to tell you more about him.

*Paid subscribers will receive a minimum of one full-access post per week, but perhaps as many as three if I’m on a roll.