The Jesuit and the civil-rights martyr

Loyola U.'s Thomas More Club lecturer, like More himself, would die for the truth

This December 10 will be the seventy-fifth anniversary of the day that the St. Thomas More Club of the Loyola University New Orleans Law School hosted an outside economics professor to address it on the “Economic Lure of Communism for Minority Groups.” Normally there would be nothing remarkable about that; then as now, it was common for Thomas More clubs—named after the English martyr-saint—to host speakers on topics of interest to Catholics in the legal field.

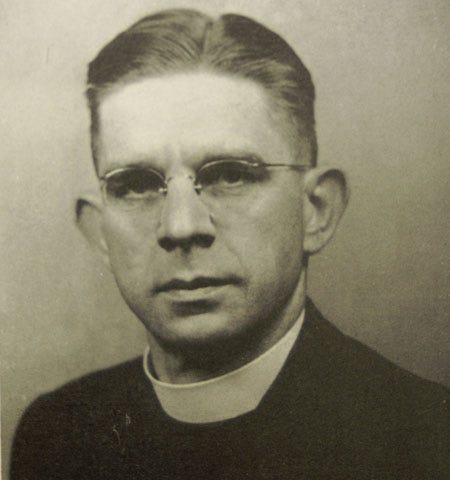

But Alvin H. Jones, the professor who addressed the assembled Loyola students on December 10, 1948, wasn’t just any speaker.

Jones was an outstanding Black Catholic academic, a graduate of the Wharton School of Finance and Commerce at the University of Pennsylvania, who, after founding the economics department at Xavier University, had become a professor at Southern University, the largest historically Black university in Louisiana. He may well have been the first Black speaker ever to grace the stage of the Jesuit university’s Marquette Auditorium, which was packed with students and faculty eager to hear him. (The audience was almost certainly all white. Two years would pass before Father Twomey dared to be the first Loyola administrator to lift racial barriers, admitting Black students into his Institute for Industrial Relations. Loyola University New Orleans then slowly began to integrate other departments, but it refused to admit Black undergraduates until 1962.)

Even if Jones only had the achievements already mentioned, he would still be an important figure in the history of Black achievements in the racially segregated South. But Jones’s work for civil rights and human dignity extended even to the shedding of blood.

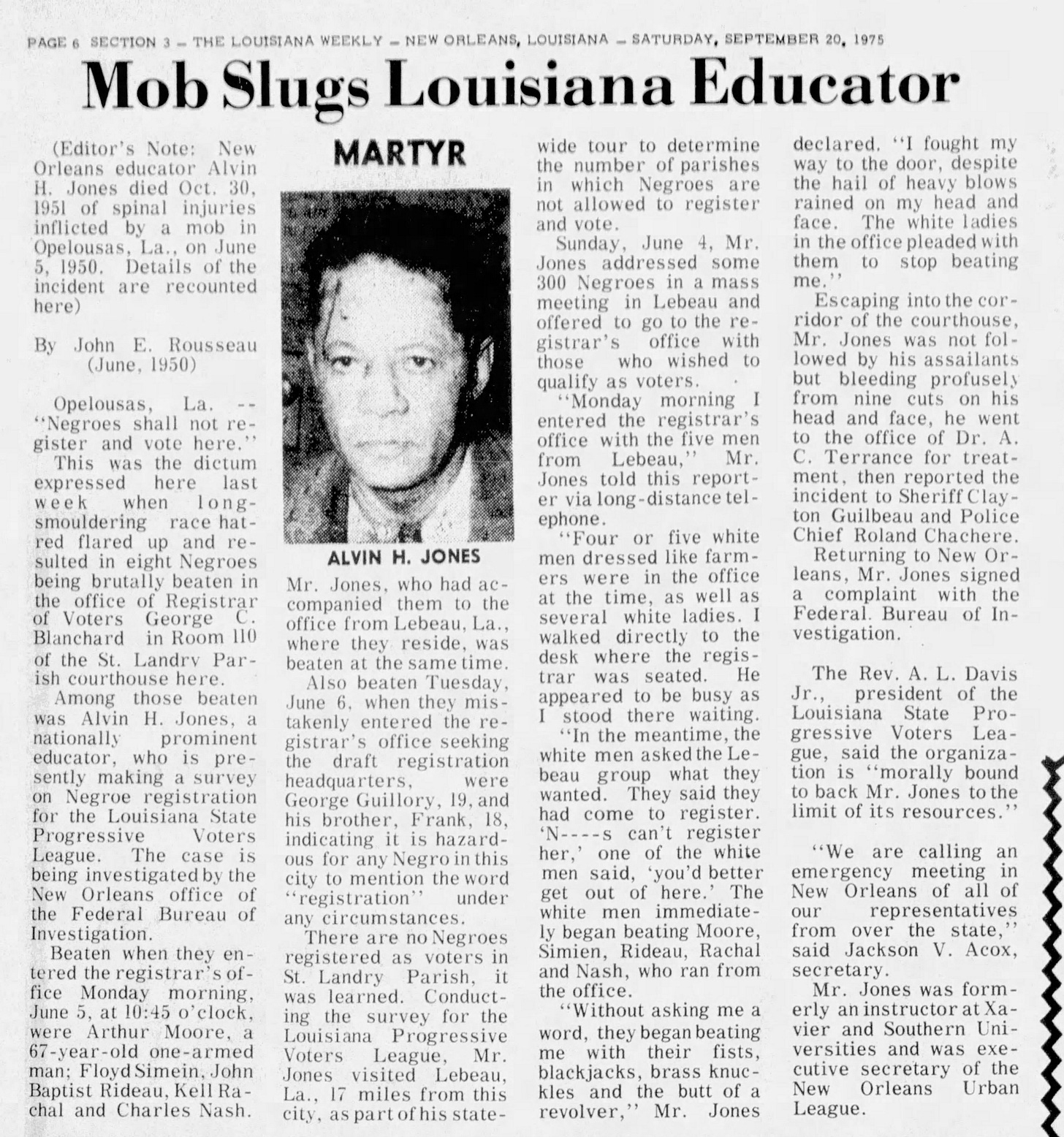

Less than three years after speaking at Loyola, on October 30, 1951, Jones would die at the age of fifty-five. The cause of his death was the spinal injuries he sustained on June 5, 1950, when he was beaten by a gang of white men inside an Opelousas, Louisiana, voter-registration office as he brought in five Black men and said they wished to register to vote.

Jones, at the time of the attack, was making a statewide tour to determine which parishes (Louisana’s term for counties) were blocking Black residents from registering to vote. On June 4, 1950, he had addressed a mass meeting of Black residents of St. Landry Parish, which includes Opelousas, and had offered to accompany to the registrar’s office anyone who wished to qualify as a voter. He was making good on his offer when he was attacked on June 5.

The Louisiana Weekly published his account of what happened in that room:

Four or five white men dressed like farmers were in the office at the time, as well as several white ladies. …

“N——s can’t register here,” one of the white men said, “you’d better get out of here.” The white men immediately began beating [the five Black men who wished to register], who ran from the office.

Without asking me a word, they began beating me with their fists, blackjacks, brass knuckles, and the butt of a revolver. I fought my way to the door, despite the hail of heavy blows rained on my head and face. The white ladies in the office pleaded with them to stop beating me.

Jones escaped into a corridor and, after his wounds healed, continued his activism on behalf of voter-registration until the effects of his spinal injuries (or, according to one report, a blood clot on his brain) brought his decline and eventually his death.

As I write my Father Twomey biography, what strikes me about the intersection of the Jesuit’s life with that of the civil-rights martyr was how Twomey, years before his friendship with Martin Luther King, Jr., was already befriending and platforming a Black leader. Part of my work in writing the book will be to show just how courageous such allyship was for a Southern Jesuit teaching at a totally segregated university in a city where public spaces were segregated by law.

I can say with confidence that, despite the speech being hosted by the St. Thomas More Club, Twomey was responsible for giving Jones a platform at Loyola. In his role as Regent of the Loyola University New Orleans Law School, Twomey was a chaplain and adviser to the St. Thomas More Club. He alone, and not the students, would have had the power to bring in a Black speaker and to defend that choice before Loyola’s faculty and staff, which at the time included numerous ardent segregationists.

Moreover, the topic of Jones’s talk was so close to Twomey’s own concerns that it was without doubt requested by the Jesuit. At that time, Twomey was working to refine an argument that would become central to his social-justice efforts—namely, that communism was an effect, rather than a cause. Its spread was fueled by inequities and could be successfully halted only by proactively working for justice. In a speech that he would deliver in many venues from the summer of 1948 onward, Twomey argued, “It is folly to think that we can turn back the tide of communism merely by damning it. This means we must take definite and positive measures to get our own house in order and thus bulwark ourselves against traitors from within and without.”

That same message, in different words, rang forth in Jones’s Loyola lecture, as reported by Father Twomey himself in the second issue of his new intra-Jesuit social-justice newsletter, Christ’s Blueprint for the South (published December 15, 1948):

Mr. Alvin H. Jones told an enthusiastic audience why communism makes such a strong appeal to exploited classes. In a scholarly address, … Mr. Jones stated that the most effective antidote to the threat of communism’s attraction for such groups is the elimination of discrimination based on un-Christian violations of social justice. “A deeply rooted religious spirit,” said he, “accounts more tellingly than any other ascribable reason for the Negroes’ resistance to the lure of atheistic communism.”

Again, part of my task as Twomey’s biographer will be to adequately convey how powerful Jones’s presence and message must have been for an all-white audience in an auditorium at a professedly Catholic university that itself practiced that very “un-Christian” racial discrimination. And, by the same token, I’ll need to convey how powerful Twomey’s account of Jones’s talk, as well as his other writings on racial justice, must have been for his newsletter’s readership—an entirely in-house Jesuit audience unused to such blunt criticism of the Society of Jesus’s practices from one of their own.

But in fact my research has already uncovered a great deal of evidence of how Father Twomey’s Blueprint inspired its Jesuit readers, some of whom went on to be the Society’s most dedicated servants of Christ’s poor. One of them will be the topic of the next post.

Thank you for subscribing! Please click the “refer a friend” button or the “give a gift subscription” button below to help me share Father Twomey’s story with more readers.