This post is the fruit of research for my biography-in-progress of Father Louis J. Twomey, SJ.

Although the Knights of Columbus’s national organization claims a “long history of promoting civil rights,” its southern chapters excluded Black Catholics for many decades after its founding in 1882. In 1909, priests of the Josephite congregation, which is dedicated to ministry to African-Americans, founded the Knights of Peter Claver to provide Black Catholics with their own fraternal order. Today, both orders of Knights are open to all. But on December 10, 1950, no Knights of Columbus chapter south of the Mason-Dixon line admitted Black members, and certainly not the one in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, which is where we find Father Louis J. Twomey, S.J., that evening.

That night, to mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of the private revelation of the Five First Saturdays devotion to the Immaculate Heart of Mary, members of four Baton Rouge chapters of the Knights of Columbus were planning to create a “Living Rosary” at the State Capitol. They had invited Father Twomey, director of the Institute of Industrial Relations at Loyola University New Orleans, to give an address on “Is the American Way of Life Worth Living?” No doubt Twomey’s reputation as a fiery anti-communist played a role in the invitation, given that an object of the Immaculate Heart devotion was the conversion of Russia.

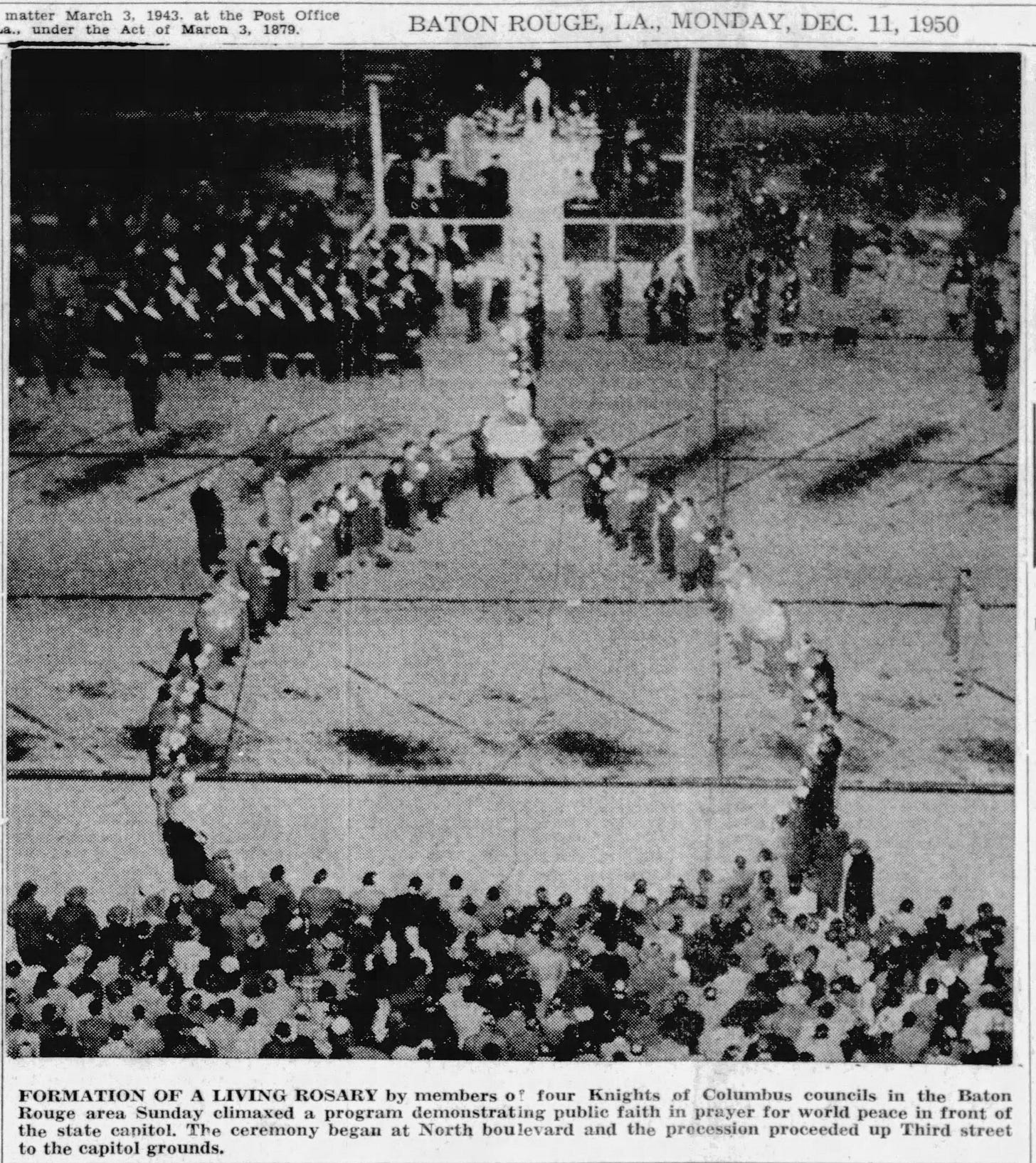

The Living Rosary would be formed by Knights of Columbus members who would each carry a light representing a bead of the rosary. After Father Twomey’s speech, there would be a mass recitation of the rosary, led by local priests, with each human “bead” turning on his light at the appropriate time. (The article shown above gives more details.) And that is indeed what happened, as a photo on the front page of the next morning’s North Baton Rouge Journal would show.

In the photo, which you can see above, there are, to the left and towards the back, more than twenty men in white sashes. They are complemented by a smaller group of men to the right, with what appear to be some women standing further off to the right. Although I can’t be sure (unless perhaps some experts in regalia come to my aid), it appears that the men on one side are Fourth Degree Knights of Columbus, whereas those on the other side are Fourth Degree Knights of Peter Claver. (My guess is that the Knights of Columbus are at left, and that the Knights of Peter Claver are at right, with members of their Ladies Auxiliary behind them.

The presence of Knights of Peter Claver at the event is attested by the Morning Advocate article shown at top. To be honest, I was surprised to see that they participated, given the segregationist policies in Baton Rouge at that time as well as the segregation that was practiced in the local Catholic community itself. There is likely an intriguing backstory concerning how Knights of Peter Claver came to be included in the event, given that it was organized by the Knights of Columbus.

I wouldn’t at all be surprised if Father Twomey played a role in gaining the Peter Claver members’ participation, as he was a great supporter of the order. But I don’t know that—at least, not at this point in my research. What I do know is that he used his speech at the event to rail against white supremacy.

“It’s time we paid attention to the havoc white supremacy is wreaking in world relations,” Twomey told the gathering. He argued that the United States seriously undermining its global witness to democracy when it failed to follow the message of its own Declaration of Independence—that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

His remarks likely made a profound impression upon the crowd; the Associated Press turned them into a national story.

Judging by the AP story, it seems that Twomey—who was himself a Knight of Columbus—was simply delivering what had, during the past year, become his standard anti-communism talk. Earlier that year, in speeches to the National Catholic Educational Association in New Orleans and to students at campuses where he toured with the Summer School of Catholic Action, he had made similar arguments. He even compared American segregationists with Adolf Hitler, telling a Detroit Times reporter in July 1950, “Three-fourths of the world’s population is nonwhite, and therefore we can’t hope to win their loyalties—and we must win them—by using essentially the same tactics Hitler used in his racism.” At that time, those were exceptionally strong words coming from a Catholic priest—or any Southern white public figure, for that matter.

But if Twomey’s words and message were similar to what he had shared before, his audience was different. Unlike the Catholic educators and college students he had addressed before, the Knights of Columbus of Baton Rouge, as a body, practiced segregation by choice. No outside executives or administrators had forced it upon them. Their Northern counterparts in the Knights did not practice it.

It therefore took exceptional courage for Father Twomey to tell them in effect that, despite their efforts to counter Russia’s errors by praying the Rosary, they—through their practice of segregation—were actually enabling communism’s spread. Only by following the “message of hope” in the Declaration of Independence, acknowledging every human being’s dignity before God, could they effectively counter the Red threat, he said. What a powerful message to give at a Knights of Columbus event where a small band of Black Catholic Knights of Peter Claver—an organization whose very existence testified to the K of C’s racism— were looking on!

Twomey’s later writings and talks bear evidence of his desire that the Knights’ Southern chapters end their policy of discrimination. In October 1951, writing in the social-justice newsletter he edited, Christ’s Blueprint for the South, he noted approvingly that the Knights of Columbus Council No. 3345 in San Antonio had become the first in the South to break the color barrier.

And in August 1957, the Chicago Daily News reported that Father Twomey, speaking to students at the Summer School of Catholic Action, criticized the Knights of Columbus for having “a policy that forced Negro Catholics to form a separate organization.”

Indeed, at the time of that speech, the Knights of Columbus in Baton Rouge were still segregated—and would remain so until 1965, when Bishop Robert Tracy persuaded them finally to end their discriminatory policy.

The final words of Father Twomey that are quoted in the Chicago Daily News article remain as relevant today as they were sixty-six years ago: “There is no such thing as white democracy, but we have perverted democracy to mean just that. There is no such thing as white Catholicism, but we have perverted it to mean that.”

If you believe, as I do, that Father Louis J. Twomey, S.J., deserves a full biography, please show your interest by subscribing to Matters Twomey, and support my work with a paid subscription if you can.